Clean Fuels and Good Intentions

One of my recurring investment rules is never to confuse good intentions with good investments. I know it’s satisfying to put your money where your mouth is, or invest out of principle, but it’s almost always best to stay dispassionate.

A great example of this is investing in transportation fuels derived from non-petroleum sources, such as sustainable aviation fuels (SAF). Aviation contributes up to an estimated 5% of global CO2 emissions, and as more people fly annually, the percentage is increasing. Given the aggressive targets that many governments have adopted to limit greenhouse gases, the quest for viable low emission transportation fuels has become critical.

After the passage of US energy and climate spending packages in 2022, clean fuel startups became all the rage. Investment firms showered them with funds, despite the fact that many of the technologies were unproven, unscalable, and had already failed to produce commercially viable results. The government’s largess allowed many startups to breathe a sigh of relief.

They were premature. On top of the existing technological challenges, ever rising costs, and pushed back timelines, the details of the government’s subsidies and tax credits were still in limbo. Reality replaced optimism, and many of the airlines and shipping companies that had set aggressive emissions targets assuming that clean fuels would be readily available had to rethink their plans or cancel them altogether. Needless to say, many of the startups closed their doors.

Only a few of the clean fuel startups went public, notably Gevo (GEVO) and Plug Power (PLUG). The latter is involved with green hydrogen, a possible fossil fuel replacement. Both stocks have been hit hard, to say the least: Plug is down 51% YTD and Gevo 40% (charts below):

Source: OptionMetrics

Source: OptionMetrics

As you would expect, both PLUG and GEVO have incredibly expensive options associated with them, with their implied volatilities priced in the triple digits. GEVO’s have been known to go over 500%. Caveat emptor!

GEVO has been rallying lately, spiking from $0.79 at the end of August to close at $1.71 last Friday. Reportedly, investors were cheered by their acquisition of a carbon capture ethanol plant and the granting of a patent regarding ethanol transformation. The cheering might be too soon – prior to the rally, GEVO was almost delisted on the NASDAQ after spending 30 consecutive days below $1.00. That’s not a great sign for those bullish on the stock.

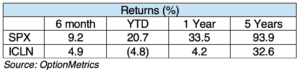

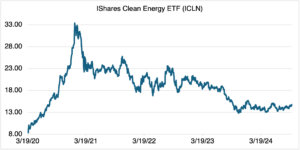

Other than green alternative fuels, clean energy investments in general (as represented here by the iShares Global Clean Energy ETF), despite all the attention and government support and direct intervention, have produced lackluster returns over the last few years, especially relative to the S&P:

Source: OptionMetrics

Again, a good cause, but not necessarily a good investment.

To Cut or Not to Cut?

One of the most frequent questions investors ask me is when to cut a losing position. Of course, the answer is almost always some variant of “it depends.” Hoping for a simple formula or rule, they are almost always disappointed. Adding to their dismay is that they are usually asking for a reason, are in the midst of a bad trade, and wondering what to do.

Over the course of my career, and regardless of the size or expertise of the firm, losing trades and what to do about them have consumed more mental energy, attention, and capital than any other topic. Preventing the issue from metastasizing into something nightmarish keeps many risk managers, consultants, and head traders up at night, and employed. Managing a bad trade or position is what separates great traders, and great trading managers, from the rest.

Retail investors can learn from what hedge funds and institutional trading desks do to prevent outsized losses. Usually, loss prevention metrics are a subset of the firm’s overall limit structure that governs trading throughout the portfolio. Limit structures can vary considerably, but in general, they include limits on position size, composition, volatility, and return. [As a side note, you may be interested to know that many sophisticated firms don’t rely solely upon sophisticated statistical models to assess their risk. Many use the common sense “worst-case” method, i.e., what is the worst return that the position has ever had historically? Trading limits are then keyed off that number). The most simple loss prevention metric is to stipulate a maximum % loss (i.e., a stop-loss), with no trade or group of trades allowed to exceed that level. Although that sounds simple enough, in practice it’s more complicated due to illiquidity constraints (the position cannot be cut, or the act of cutting itself increases the loss) and related valuation difficulties.

For retail investors, I can provide some very informal advice. First, if you specify a stop-loss, stick to it. There are always reasons to hang on for another day, but they rarely pan out – cut the trade, learn from your mistake, and move on. If the trade is keeping you up at night, or you are praying for a recovery, or are afraid to tell your spouse, or the loss could possibly impact your lifestyle or financial well-being, then you’re in over your head and it’s time to get out. Remember, you aren’t a professional trader; the object is to make some extra income or manage your savings, not to let the loss take over your life.