Prediction Markets: Who Knows?

Last week, I wrote about the effect of presidential elections on the equity markets (hint: the effect is minimal). Now the election is finally upon us, and the polls still show a dead heat, +/- a few points one way or the other. They haven’t budged since a few weeks after Harris became the nominee. Since the 50/50 split seems to be locked in, the only thing to do now is to await the eventual winner. In the meantime, the election has turned out to be the fundamental that isn’t.

But, is it really a dead heat? I’ve written a few times about the rise of predictive markets, i.e., markets in which you can bet on the outcome of certain events. Elections, sports, finance, pop culture — if it’s uncertain and in the future, you can bet on it. Polymarket, Predictit, ForecastEx, and Kalshi are popular examples, although new ones are springing up all the time (Robinhood just announced one).

Since traditional opinion polls were wrong in 2016 and to a large extent in 2020, they have fallen into disrepute. That opened the door for the introduction of prediction contracts on regulated exchanges. The CFTC tried to ban them, but was blocked by an appeals court in early October. Now the floodgates are open.

The current crop of prediction contracts are “yes/no” contracts, priced according to the estimated probability of each event occurring. For example, one of the questions on Kalshi is “who will win the Presential election?” Currently, Trump is trading at 62% and Harris at 38%. If you bet on Trump, you will pay $0.62 cents; if he wins, you will get $1.00 (the max payout); if he loses, you will lose your original investment, $0.62. There are some quirks between the different platforms. For example, Polymarket, the largest by far of them all, is only available offshore and trades only in stablecoins. Since the products aren’t the same and aren’t standardized, you can’t take advantage of the different probabilities by trading on different platforms. Too bad.

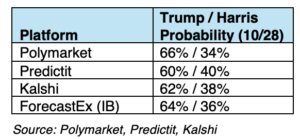

Interestingly, the predictive markets are contradicting polling results. Since early October, they have been showing ex-President Trump as the clear favorite to win the election:

The trend is clear and similar on all platforms:

The obvious question: why the disparity between traditional polling data and predictive markets? First, a few comments:

1. The sample size for analyzing presidential elections is very small, whether one is using polling data, predictive markets, or tea leaves. As I wrote last week, “Since 1980, there have been only 11 presidential elections, and since the introduction of the Dow in 1896, there have been just 33.”

2. Predictive markets have come and gone over the years – it’s hard to keep interest in them during non-election years – but have really only existed since 2020. Statistically, there just isn’t enough data to say whether predictive markets are more accurate than polling data or not.

3. Intuitively, it seems that predictive markets should outperform polling methodologies. Putting your hard-earned money on the line should produce a more accurate and thoughtful answer than not. It’s similar to the difference between paper trading and trading with real money. The former can be fudged, and you don’t have to take your trades all that seriously; if you’re wrong, you don’t lose any money. Real trades, ones in which you can lose real money, forces you to make more careful and considered predictions.

4. Speculation that the predictive markets have been manipulated by a few large traders, and therefore the results are inaccurate, is overblown. Anyone is free to trade. If you think a Harris victory has been underpriced, buy it. Also, the charge that the markets are thin and therefore relatively easy to manipulate (by so-called “whales”) is only true as long as illiquidity is present. Currently, the Polymarket Trump v. Harris bet has almost $2.6 billion in trades outstanding; the Predictit version traded 57,000 contracts last Friday. These aren’t giant markets, but large enough that sustaining prices at unnatural levels on all platforms for more than just a few trading sessions would be extremely difficult, and expensive. Successful manipulation is a lot harder than it seems.

5. Bolstering this view is that all of the predictive markets have trended the same way since early October and are showing similar results. Manipulating several markets at once to produce similar results, and keeping them there over several weeks, is unlikely.

The question of the wide disparity between polling and predictive data remains. Frankly, since this is the first time such a comparison can be made, we’re left with only guesses. Although polling results involving Trump have been notoriously inaccurate, pollsters have had several elections and eight years to correct the polls’ methodologies. At the same time, predictive markets may be processing new information faster than the polling models can be updated. Eventually, the polls will catch up (although at this point, they’re running out of time!).

On the other hand, predictive markets may be biased. Although the exact demographic of who trades them is unclear, it seems that they may be attracting traders that are not broadly representative of the general electorate, i.e., overwhelmingly male, very online, very political, and crypto-oriented. In other words, biased towards Trump.

Most likely, the true results are somewhere in the middle, with Trump’s odds higher than the polls indicate but at the same time lower than where the predictive markets are trading.

Only one thing is for sure: a new President will be elected on November 5th, and despite all the gloomy predictions to the contrary, the Republic will survive.